“No force on earth can stop an idea whose time has come” – Victor Hugo

On 24 October 2019, the Government of Pakistan suspended implementation of Highway Safety Ordinance (NHSO-2000) for one year. Ministry of Communication has to this day not issued a formal notification; only Dr. Ashiq Awan, Minister of Information (and Govt. of. Pakistan official Twitter Handle) did tweets informing the public that the Prime minister has instructed Frontier Works Organization (FWO) to suspend implementation of Axel Load Regime, on M-9 (Karachi-Hyderabad Motorway) for one year to facilitate traders on M-9.

There is an interesting background to all this. Implementation of NHSO-2000 had been pending for the past 19 years. Four regimes and seven prime ministers have changed since then. Still, none could muster the strength or conviction to speeding emerged as the principal culprits behind fatal accidents. The curtain was raised when, after a series of meetings with transporters and chambers of commerce, other stakeholders, and after series of advance advertisements in major newspapers, Murad Saeed, Minister of Communication, set the cat among the pigeons.

He announced – what was unthinkable for 19 years – that as of 1 June 2019, the Government was implementing the Axle Load Limit policy, as set out under the National Highway Safety Ordinance (NHSO) and the ministry would be the executing agency for this policy. Communication ministry had recommended the implementation of the policy to control the number of accidents, deaths and minimize the damage borne by Pakistan’s national highways.

Before implementation, a technical committee was formed consisting of officials from the Ministry of Communications, and the National Highway Authority (NHA) that held a series of meeting with stakeholders such as the Goods Transport Agencies, Trucks Drivers Association, and key sectors of the industry – but it probably never correctly estimated the financial burdens that will be faced by the industry (especially Cement, Steel, Sugar & Brick Kilns) in a slowing economy.

Implementation, starting from Karachi upwards, continued for precisely 20 days before an enraged industry was able to prevail upon the Prime Minister for its suspension. The matter soon landed in Islamabad High Court. The NHSO Ordinance was introduced in 2000, under Musharraf’s Government. But could not be implemented for almost 20 years; the Nawaz Government made the last serious attempt in implement a law creating road standards that has become the norm all across the region (including Iran and Afghanistan).

Read more: NLC’s Freight Train (NEFT) points the way forward for Pakistan

On different occasions, governments tried implementation but then surrendered to resistance from industry and transporters. So, it was definitely ambitious and forward-looking when the young communication minister of the new PTI government (Murad Saeed) started working on it as early as September/October of 2018. Murad Saeed’s team at the Ministry of Communication was mainly focused on “Road Safety” – where overloading and 2013.

But it faltered again due to influential lobbies representing the combined strength of industry and goods transporters. Murad Saeed’s bold decision could only happen because, by the year 2019, transporters got convinced that they could make more money if the law (NHSO -2000) is implemented – and that industry had been using them all along in a cause that was never theirs.

So, when the PM suspended its implementation on 20 June, Transporters – who had emerged as separate stakeholders seeing profits – went to Islamabad High Court seeking directions for implementation. What non-implementation of NHSO-2000 means? The ordinance, as pointed out above, first brought by the Musharraf government in 2000, was never implemented due to stiff resistance by both truckers and the industry.

Under Section IV of the ordinance, the Government may, in consultation with National Highways and Pakistan Motorway Police, by notification in the Official Gazette, make rules regarding the construction, equipment, and maintenance of motor vehicles, trailers, bicycles, and animal-drawn vehicles.

Therefore, granting it the authority to establish the width, height, length, and overhead of vehicles and the loads to be carried therein. No person shall drive or cause or allow to be operated on a national highway any motor vehicle for which the axle weight exceeds the maximum axle weight specified for that axle in the certificate of registration. (See Figure 1).

The lack of enforcement of this law has meant that: in Pakistan, if a standard triple-axle truck with a double axel is supposed to carry 38 tons of payload (weight of goods being transported), then on average most trucks carry easily 40-45% payload above that. The cost of these overladen vehicles is borne by many stakeholders, including truckers, truck owners, transport industry, infrastructure authorities (like NHA, FWO, and NLC), but above all, the general public and taxpayers. Pakistan, in recent years, has spent $ 150 billion on roads through the National Highway Authority (NHA).

Most of these roads, highways, and motorways are being eroded and damaged by overweight trucks increasing the cost of maintenance, which is borne by the Government. The average cost of construction of the standard highway is around Rupees 60 million per kilometer. The NHA reports that it spends around Rs. 65 billion on road maintenance each year (on roads maintained by them alone).

Axle Loads in the Region

Pakistan, ironically, is now the only country in the region where trucks still fail to abide by the limits set by the Government on axle load limits. Neighboring states such as Iran, Afghanistan, and India have strict regulations to ensure the implementation of such laws even though their limits are far more stringent than what is permissible in Pakistan.

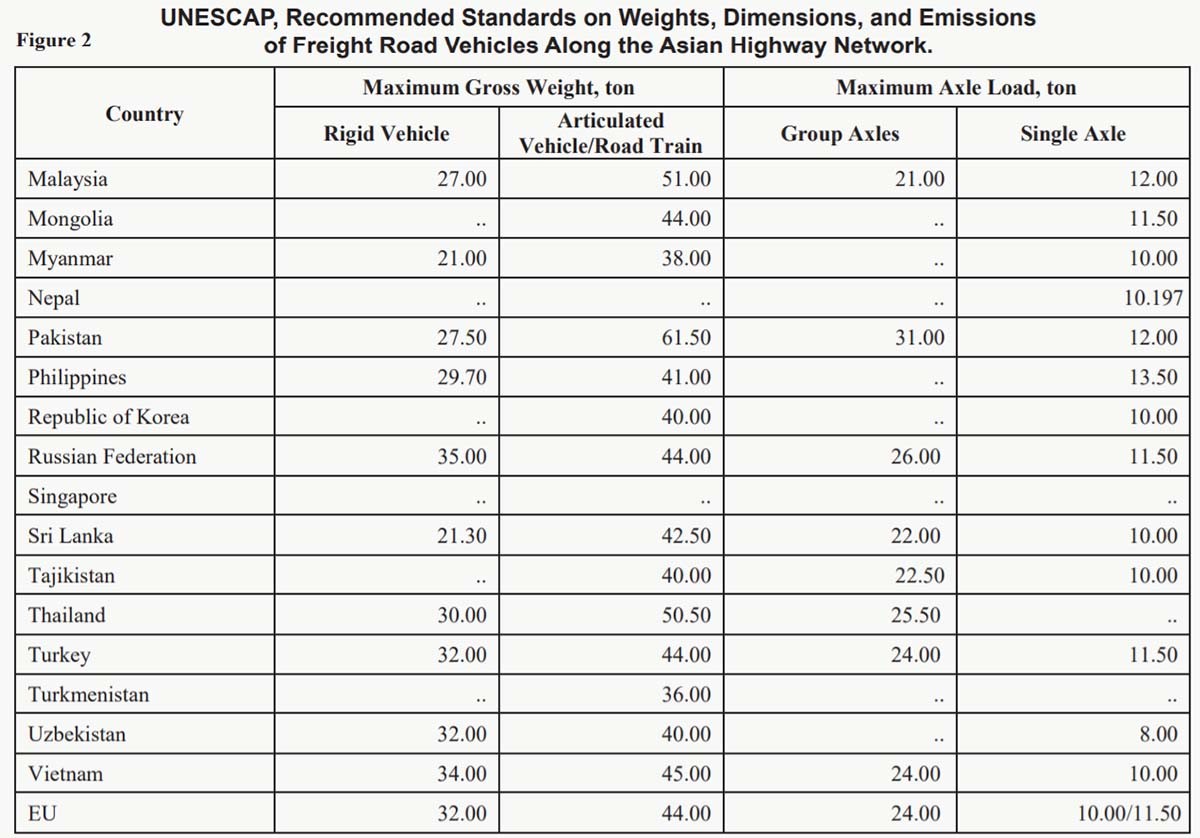

For example, for a six-axle tandem-tridem, India allows 55 metric tons and Afghanistan only 49 metric tons per axle while Pakistan’s legal axle load stands at 58.5 metric tons. The United Nations Economic and Social Commission of Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP), which acts to promote cooperation among countries to achieve inclusive and sustainable development, recommends 12 ton per single axle for vehicles in Pakistan.

This recommended value differs based on a country’s legal, economic, and environmental conditions. Another chart (See: Fig 2) shows a comparison between the recommended weight for Pakistan and other Asian countries.

Currently, what is happening in terms of regional trade is that when Pakistani trucks reach international borders such as the Torkham border with Afghanistan, the truck has to offload its goods into two vehicles to travel into the other country.

These were the facts and circumstances upon which a judge of Islamabad High Court (Justice Miangul Hassan Aurangzeb) applied his mind in the first week of July 2019 – leading to an interim order for continuing implementation. However, in August 2019, the sugar and steel industry representatives approached the Sindh High Court with counterarguments.

They demanded: either exemption from the policy for several months or cancellation of the sixth schedule of the national ordinance 2000 or grant of a stay order. Court denied the stay order, but the matter was admitted for hearing. Nothing further has been decided so far. Failing to obtain relief from courts, pressure was then put by businessmen on the Prime Minister and Army Chief in meetings.

Read more: Pakistan’s Border Trade Issues Reducing its GDP Potential

Industrialists claimed, with some credibility, that immediate implementation of the Axle Load Limit Regime was technically not possible, as not enough trucks existed in the country to carry cargo, and even if it is done, somehow, it would raise industry’s cost of transportation of raw materials and finished goods. This, they pointed out, will not only increase consumer prices but would also hit exports that Government was trying to promote.

Industry claimed that truckers had raised costs per metric ton. And at least one credible source from the trucking industry told GVS, during July-August, in which the Axle Load Limit Regime was being enforced, that for practical purposes price of truck services to the Industrial sector had risen by 40% (perhaps due to using two trucks instead of one, and minimum costs per vehicle increased)

Government: Fears of inflationary pressures

On 24 October 2019, the industrialists prevailed, and the Government – by that time, afraid of inflationary pressures – suspended implementation of the policy for one year. Jumps in prices of vegetable oil, ghee, cement, fertilizer, steel bars, and vegetables were blamed on high transportation costs.

After a meeting with businessmen, a statement by the Prime Minister confirmed the Frontier Words Organization (FWO) would suspend the implmentation of the axle load weight limit on M9 (Karachi to Hyderabad) motorway for one year. On 21 November, Islamabad High Court completed its proceedings, wondering how the Government can suspend the implementation of this law?

However, a detailed judgment is awaited that will clarify what the court has directed. Axel Load Limit law thus clearly represents a catch-22 situation where a government wants to make progress in a positive direction necessitated by demands of future but is hamstrung because it is unable to disentangle the politics of different interest groups.

Truckers: Challenges of Life, Liberty & Insurance?

Speaking to GVS magazine, Awais Chaudhry, the General Secretary of the All Pakistan Goods Transport Owners Association, explained how the non-implementation of the axle load policy has severely affected both the trucking industry and the general economy. He argues that the high loads that trucks carry impose a severe mental and physical toll on drivers, their vehicles, and on roads.

The Transport Association highlights the increased risk of accidents that comes with loading trucks above the axle load limit. Truckers are coerced into carrying cargo heavier than the permissible limit because of high competition in the truck industry. To ensure that a vehicle can carry a much higher load, they are often fitted with extra axles and leaf springs.

Read more: Imposition of IMO-2020 standards: Pakistan should brace for impact

If a trucker demands to take lighter cargo for a given price, industrialists find his competitor who is willing to carry twice the weight for the same price. This is particularly the case, as is highlighted by Awais Chaudhry, in his interview, when the supply of trucks is higher than cargo. In the event of an accident, not only is human life put at risk, but the owners of the vehicle are held responsible for the losses.

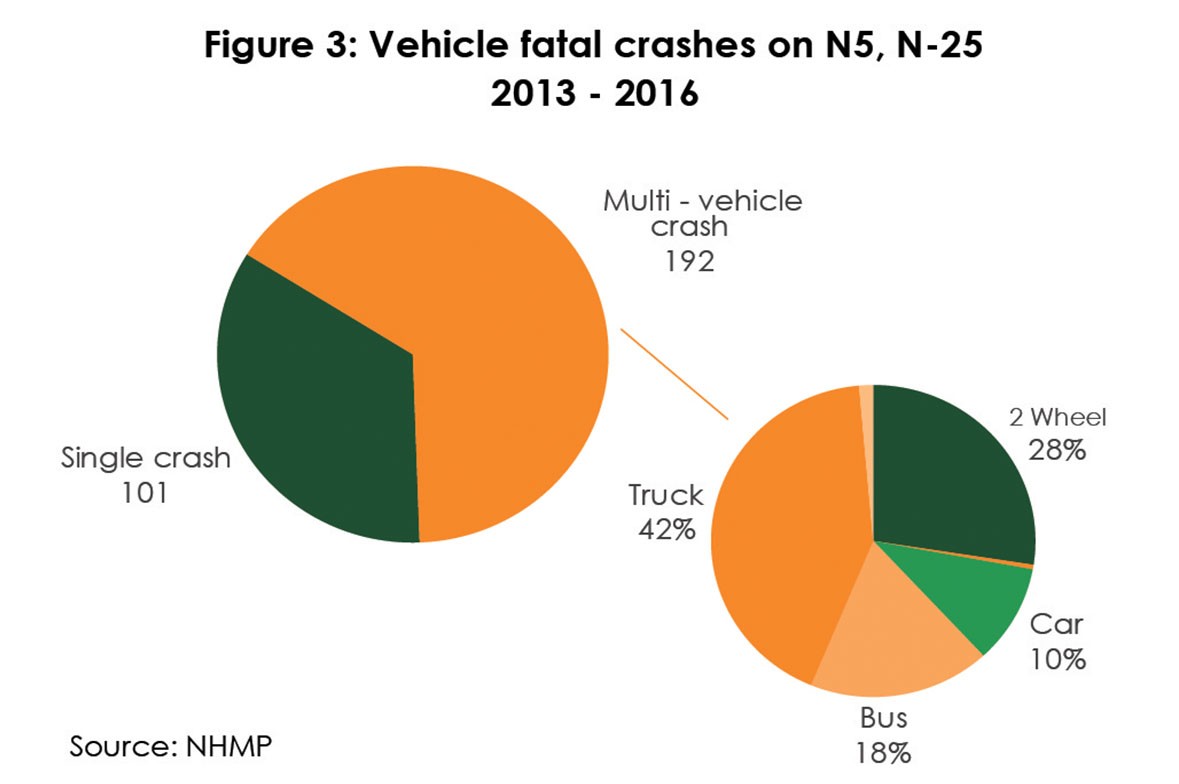

Figure 3 shows between 2013-2016, there were 645 fatal crashes involving a truck on the N5 and N-25 national highways; of these, 571 (89%) were multi-vehicle crashes involving another truck or bus. The N5, which runs from Karachi to Torkham, carries 65% of Pakistan’s commercial traffic.

According to the National Highways Safety Ordinance 2000: if a person suffers death, or injury to this person or damage to his property on account of the use of a road vehicle on a national highway, the insurance company, or as the case may be, the Pakistan Transporters Mutual Assistance Co-operative Society, the Pakistan Automobile Association, or any other road transport co-operative society referred to in section 41 of the ordinance, and in case the vehicle is not covered by any of the above insurers, the owner of such vehicle shall pay such compensation as may be prescribed by the Government.

There is no effective system of insurance in Pakistan. Generally, neither the trucker nor the product dispatchers buy insurance cover for their goods. It is especially true for those owners who have old trucks, as is the case by most in the industry. Compulsory insurance by both parties is something that the Government should implement. It will also have the added benefit that it will develop a new segment for the general insurance sector in Pakistan.

Read more: NLC Pakistan goes international with launch of Marine Services

Another major issue of the high load trucks is the effect they have on Pakistan’s roads. While highways in Pakistan are constructed and maintained under the conditions set by the ASHTO International standards, they suffer from heavy wear and tear and require constant maintenance not found in other countries, and this is mainly due to the heavy loads carried by trucks.

The international bracket for axle load is between 8.5 to 12 tons per axle. Pakistan allows the maximum limit of 12 tons per axle for a single axle, 11.5 tons for a double axel, and 11 tons for a triple axel. As specified in Figure 1, the maximum weight for a 22 wheeler six axel tandem is 58.5 tons. This vehicle represents the majority of trucks that transport cargo in Pakistan.

However, Pakistani trucks often carry over 100 metric tons at a time. Pakistan’s roads bear the direct impact of axle loads above the legal limit. One extra kg of weight on the axle doubles the impact on the road, and every additional kg above that multiplies the damage at four times the amount of pressure asserted.

Awais Chaudhry explained how the relatively new M9 national highway, which runs between Faisalabad and Karachi, which was constructed by FWO in 2018, already requires maintenance, due to the heavy loads carried by trucks. Internationally, roads generally require their first maintenance, five years after construction. Yet the M9 has already seen three maintenance operations. This is in contrast to the M1 and M2 that have remained in good condition due to the strict implementation of axle limit laws, which are not observed on M9.

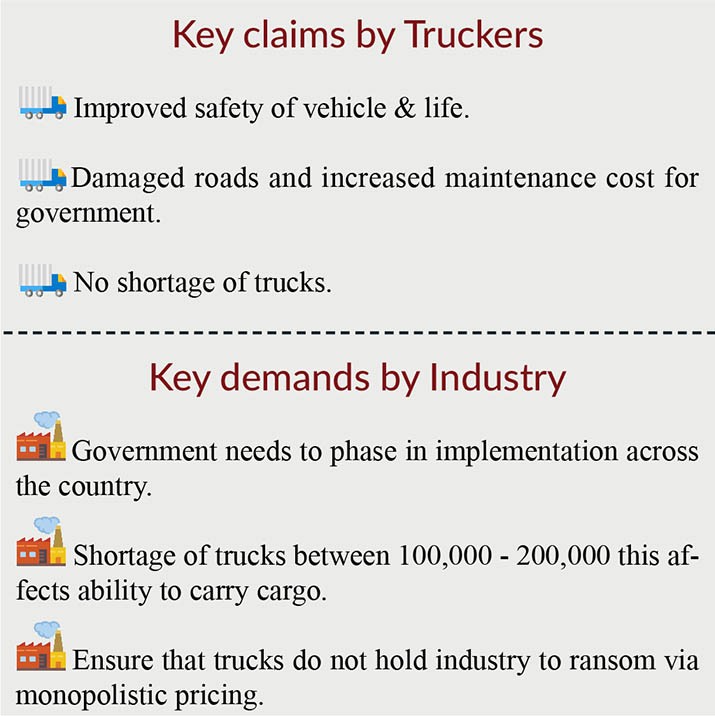

Transporters dispute the argument presented by businesses that there are not enough trucks. They have pointed out in government meetings that the decline of imports in the past one year by 30% has freed up many trucks. Similarly, as the country has moved towards phase 2 of the CPEC projects, vehicles that were earlier used for carrying construction material are now in surplus.

Industry has genuine concerns

Currently, a significant disagreement stands between the All Pakistan Goods Transport Owners Association, other truckers, and industrialists that require large consignments of their cargo transported through trucks, such as cement, steel, sugar, and edible oil. In 2018, close to 150m tons of steel and cement were moved in Pakistan – this is close to 45% of all cargo.

They calculate the implementation of the axle load regime will cost them an additional Rs.154bn. Industry representatives have expressed disquiet with the overnight government implementation of the ‘Axel Load Limit.’ In principle, the industry now accepts that the Axel Load Limit Regime is needed.

But the argument is that it was done without proper planning, no time is given to industry or truck market to adjust to the realities, creating severe problems to an already troubled industry suffering in the economic downturn the country is in the midst of. Furthermore, it was introduced in different areas affecting players in the same sector differently. So, for example, it was immediately launched in Karachi, motorways, national highways monitored by NHA, or areas where weigh stations existed but was not implemented on provincial highways.

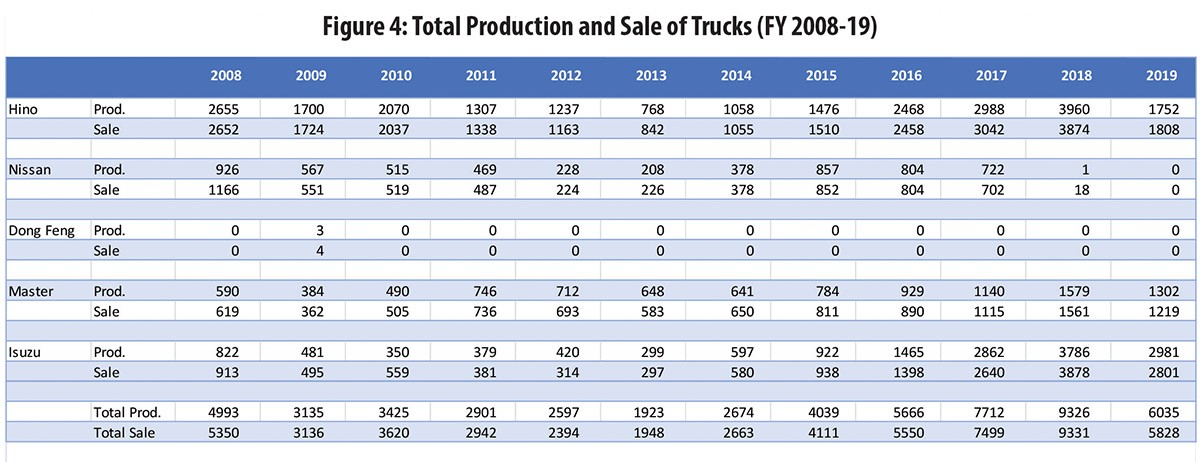

Currently, Pakistan has around 330,000 trucks in the market – many of which are very old. On average, they carry close to 100 tons, almost double the legal limit and nearly three-four times the weight the trucks are meant to carry. After the implementation of the axle, policy commerce chambers estimate that there will be an additional requirement of close to 200,000 trucks.

Domestic truck production is currently around 9,000-10,000 units– thus, a dire need to import vehicles will present itself, which is estimated will cost around $12-15bn. Industry representatives have held meetings with the Prime Minister and Chief of Army Staff to explain how the policy would negatively impact their businesses in terms of cost and availability of transport.

Read more: Modified Mehran Pickup: Pakistan’s New Social Media Sensation

Trade bodies such as the Federation of Pakistan Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FPCCI) reports that industries such as steel, sugar, fertilizers, rice, coals, cement, etc. will see an exponential rise in freight costs if the policy is implemented immediately. Abbas Khan, from Askari Cement, pointed out to GVS magazine that after the implementation of the road axle load limit, transporters jacked up prices of goods carried.

For Askari cement, he shared that earlier, if the freight cost from its plant in Nizampur was Rs. 60 per bag to Gujranwala and Rs. 70 to Lahore, after implementation of load limit prices, increased to Rs. 90 and Rs. 110 per bag to respective cities. Transporters refused to carry goods at old rates claiming that the government had reduced their volumes carried; however, their costs, per truck, remained the same.

He also pointed out that after the implementation of the load limit was enforced cost of freight went up from Rs. 1400 ($ 9) to Rs. 2000 ($13) per ton; however, currently, the government is not strictly enforcing it – truckers have only reduced it down to Rs. 1800 ($12) per ton. Their argument is they are paying ‘penalties’ if they get stopped and there are carrying more.

FPCCI (Federation of Pakistan Chambers and Commerce) calculates that agriculture will be hurt, from the reduction in the supply of DAP and fertilizer, due to fewer trucks to carry it, which in particular will hit exporters of fruits, they have estimated the cost of around Rs. 88bn annually. The brick kiln industry, which has gone to Peshawar high court for a stay order, has estimated that the reduction of the axle load will reduce the number of bricks they can load on a single axle vehicle; it will be reduced by half from 10-11,000 bricks to less than 5,000 bricks.

President Islamabad Chamber of Commerce, Ahmed Hassan Moughal, has stated that there would be a 25 percent cost of transportation increase, as well as a rise in fuel consumption, due to decreasing axel load limit. He said that ultimately, this cost would be passed onto consumers as the manufacturers would have to increase the number of trucks.

Read more: Has Pakistani Government stopped implementing Axel Load Limit Law?

Industry bodies have claimed that an extra $4-$5bn will be needed to import oil for the additional trucks on the road – once the law is implemented. However, their calculations do not account for current vehicles that are already using 50-60% more fuel due to overloading they do.

During their meeting with the PM and army chief in September, businessmen suggested that the Government increase tolls on the roads so that it covers the wear and tear cost of maintenance. Ironically, as the industry is aware, the country has around 300,000 km of roads across the country, whereas National Highways Authority (NHA) jurisdiction is only 12,000 km. However, these carry about 80% of commercial traffic.

Way Forward for Industry, Truckers & the Govt

Given Pakistan’s need for increased regional trade with its neighbors and growing demands to follow international standards, it won’t be possible to delay the implementation of Axel Load Limits for very long. Also, now there is a growing awareness in the government, judiciary, media, and policymaking circles of the recurrent costs on-road and machine maintenance, issues of safety, medical and insurance expenses, and the climate change and sustainable development needs of the country.

All these factors will make it impossible for the industry to keep delaying these internationally accepted standards. Given the large extra quantities of trucks required, in the near to medium term, Govt will have to incentivize a policy for truck imports. They should ensure that a situation is not created in which existing truck owners can hold the industry to ransom with monopolistic prices due to a reduction in truck availability versus industry needs.

The auto industry will benefit from increasing truck production domestically, which will also help to increase economic activity within the country. Furthermore, decision-makers will have to work with banks to see how they can be encouraged to launch truck financing schemes. Additional trucks will require additional drivers, thus creating new job employment opportunities for drivers and benefiting their families – thus overall creating higher economic activity in the country.

The offset will be that the domestic industry that was used to paying less will have to adjust the new increased transport costs into their profitability, or if passed through to consumers, suffer consequences of fall in demand for their products. Pakistan has some of the lowest transportation rates in the region.

One truck fleet source has estimated this at Rs. 3200 per kilometer. It is pertinent to note that already currently, many multi-nationals and large logistics providers such as NLC (largest trucking company in Pakistan) already using the weight as put down in law under the axle policy.

Read more: Karachi’s transport crisis: Blue Line on hold as Green Line project’s track is completed

Given the complexity, due to conflict of interests, the Government needs to set out a clear path for the industry and the truckers to understand that the policy will be implemented over phases and set out a time framework by which this will be done. Pakistan needs an overarching transport and logistic policy vison and well-defined framework that envisions the development of freight trains, and inland waterways (through canal system) to ease pressure on trucking and motorways.

Currently, almost 90% of freight is being carried across Pakistan through roads – while across the world, railways and water-borne trade is nearly 50% of the mix. Prime Minister, Imran Khan, has constituted an Intra-Ministerial Committee consisting of Communication, Commerce, Industries, Railways, and Finance to come up with a plan for implementation, after negotiations with all stakeholders. Much will depend upon the research, imagination, diligence, and negotiation skills of this committee.

Najma Minhas is Managing Editor, Global Village Space. She has worked with National Economic Research Associates (NERA) in New York, Lehman Brothers in London and Standard Chartered Bank in Pakistan. Before launching GVS, she worked as a consultant with World Bank, USAID and FES and is a regular participant of Salzburg Forum. Najma studied economics at London School of Economics and International Relations at Columbia University, NewYork. she tweets at @MinhasNajma.