Pakistan’s economy is known for its boom and bust cycles prevalent every five years. One of the major causes behind this is the mismanagement of its balance of payments. The country has seen no rise in its exports past several years but has taken twice as many imports. While there are several factors behind Pakistan’s imports, one of the primary reasons has been that the country imports approximately 80 percent of its crude and refined petroleum products.

In 2017-18, this amounted to USD11.9 billion for crude oil imports and over USD2.5 billion for gas. LNG Gas imports have exponentially grown since they first started in 2014-15 from 472,503 TOE (tons of oil equivalent) to 7,492,597 TOE. The country’s dependence on imported oil and natural gas for its energy consumption is higher than the average global dependence.

It is one of the highest gas dependent countries in the world and has not been self-sufficient in gas since the mid-1990s. In 2018 in India, by comparison, energy imports were only equal to 46 percent of its total primary energy consumption. It is also much less dependent on natural gas in its energy consumption, which accounts for only 6 percent, oil at 30 percent, and coal for 56 percent.

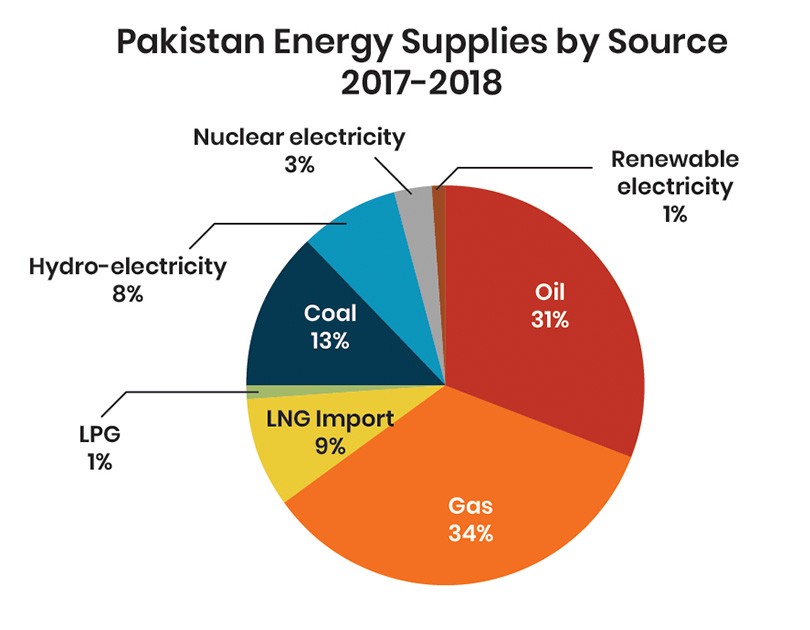

Pakistan energy supply mix

According to the 2018 Pakistan energy yearbook, Pakistan’s energy mix consists of 88 percent fossil fuels (34% Natural gas, 31% Oil, 13% Coal, 9% imported LNG and 1% LPG), and 8% hydropower and 4% other. Pakistan’s total energy supplies grew by 8 percent from a year earlier from 80 to 86 million tons of oil equivalent, and consumption grew by 9.7 percent year on year.

Reserves can change annually with discoveries, through appraisal of existing fields, and production of existing resources.

The oil and gas industry is categorized into three segments: upstream, midstream, and downstream sectors. The upstream part is also known as the Exploration & Production (E&P) sector, which consists of discovering and producing crude oil and natural gas. In Pakistan, the major players in the market include OGDCL, PPL, MPCL, and UEPL.

The midstream involves processing hydrocarbons into petrochemical products. It includes refineries, fertilizer, and petrochemical plants. The downstream sector consists of the marketing and distribution of oil and gas to the end-user in residential, commercial, and industrial sectors.

Pakistan’s proven energy reserves

According to the 2018 Pakistan Energy factbook, the country has recoverable oil reserves of (1,247 million barrels), gas (57.4 Trillion Cubic Feet (TCF)), and coal (186 billion tons). Out of the total 57 TCF of gas discovered so far, 38 TCF has been extracted, leaving 19 TCF. These remaining proven reserves are expected to last for a further 13 to 14 years.

Proven reserves indicate the amount of a resource that can be produced economically under current prices and technologies. Reserves can change annually with discoveries, through appraisal of existing fields, and production of existing resources. Pakistan’s most recent sizeable gas discoveries (considered higher than 1tcf) were Qadirpur, Sindh, in 1995, and later Gurguri, KPK, in 1998.

Read more: Pakistan’s gas sector attracting huge foreign, local investment

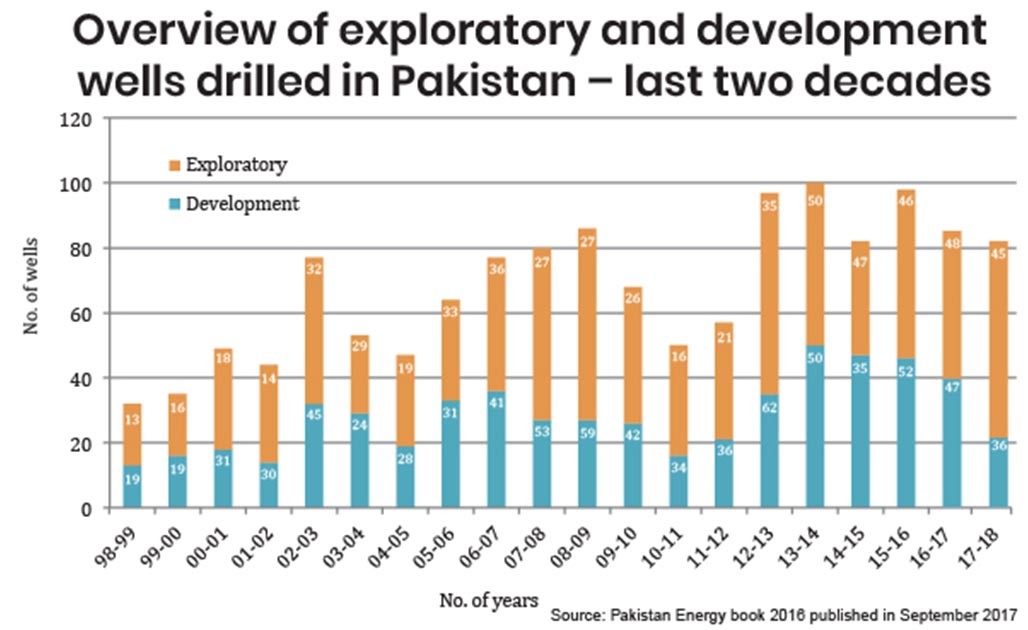

As of July 1, 2018, the country had over 1,066 exploratory wells and 1,384 development wells. Exploratory wells are those dug where gas or oil is suspected to be there. They are termed development wells when something is discovered. To date, the country has made 371 discoveries: 93 Oil wells and 278 gas/ condensate wells. Pakistan has an extremely low exploratory drilling density of one well per 810 sq km compared to the world average at ten wells per 1,000 sq km.

However, the country’s overall success rate stands at 1:2.9 wells drilled. It is considered high by worldwide standards (which stands at 1:10) – but this as an industry source put it – is because we are very generous in what we call success – so even the smallest of gas/oil discovered over a short period has been classified as a success.

In the last year, we have seen extensive activity in the upstream sector where 45 exploratory and 36 development wells were drilled out, of which 14 discoveries of gas/condensate were found.

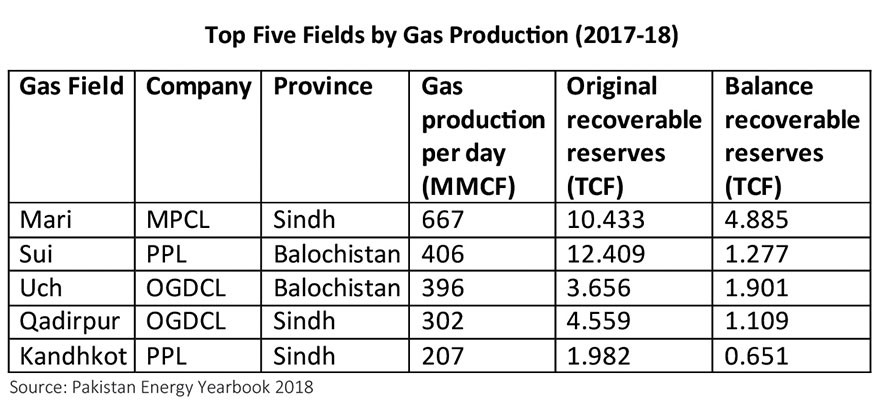

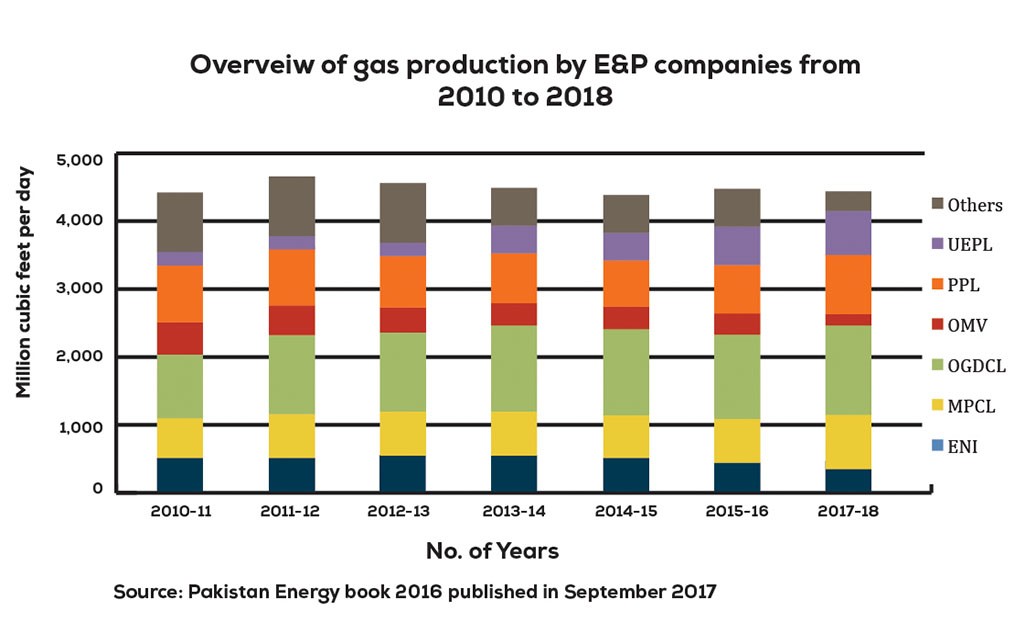

Gas production

The current domestic production of gas currently meets around 67 percent of domestic consumption, with output at 3,997 million cubic feet (MCFt) per day. It demands approximately 6,000 MCFt per day, which with increased population and growth, is expected to double by 2030. As for petroleum products, domestic production only meets 15 percent of the total demand.

As of July 1, 2018, the country had over 1,066 exploratory wells and 1,384 development wells. Exploratory wells are those dug where gas or oil is suspected to be there. They are termed development wells when something is discovered

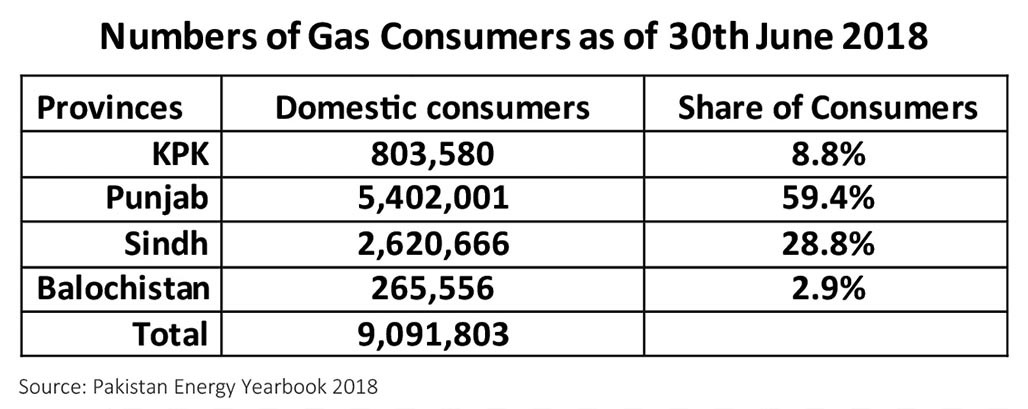

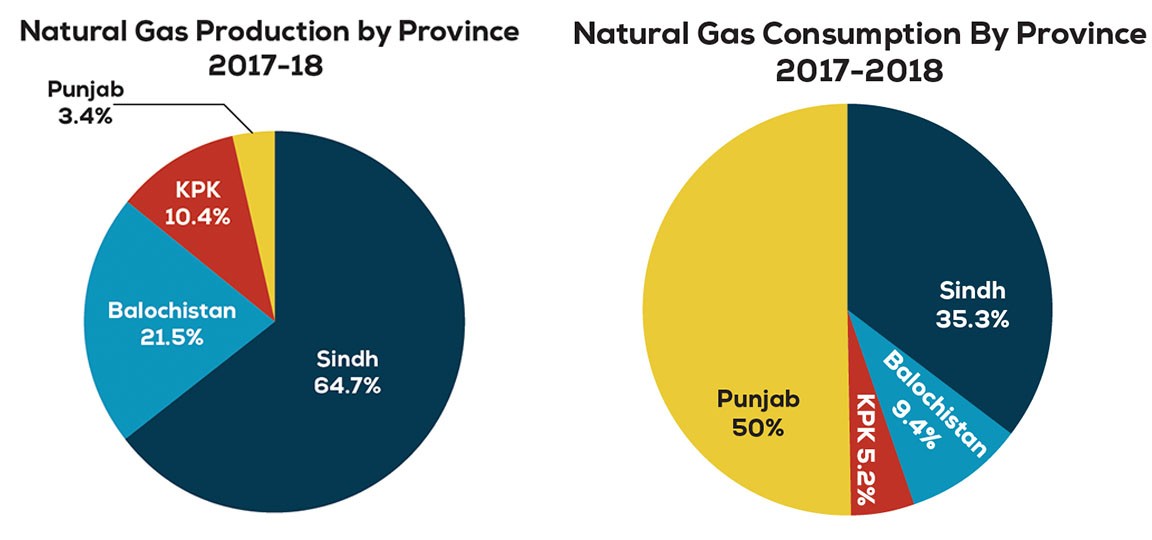

The country used 28.1 million TOE of petroleum products in FY18, with 85 percent imported. Currently, Pakistan has a total of 9 million gas consumers in the country, with an annual addition of 0.5 million consumers. Sindh by far has the country’s largest gas production at 943,644 MCFt (65%), Balochistan at 310,535 MCFt (22%), KPK at 151,178 MCFt (10%), and Punjab 53,580 MCFt (3%).

Sindh also has three of the current largest fields producing gas, Mari, Qadirpur, and Kandhkot. Sui gas field in Balochistan, discovered in 1952, was Pakistan’s first and largest gas field found so far, had around 13 TCF of gas. It currently only has one TCF remaining and is nearing the completion of its life. These five fields represent over 50 percent of Pakistan’s recoverable reserves.

Gas Consumption

Pakistan has experienced major energy crises in the past decade as a result of expensive fuel sources, suffering from chronic natural gas shortages in the winter and electricity shortages in the summer, all exacerbated by the circular debt, and insufficient transmission and distribution systems over the past several years.

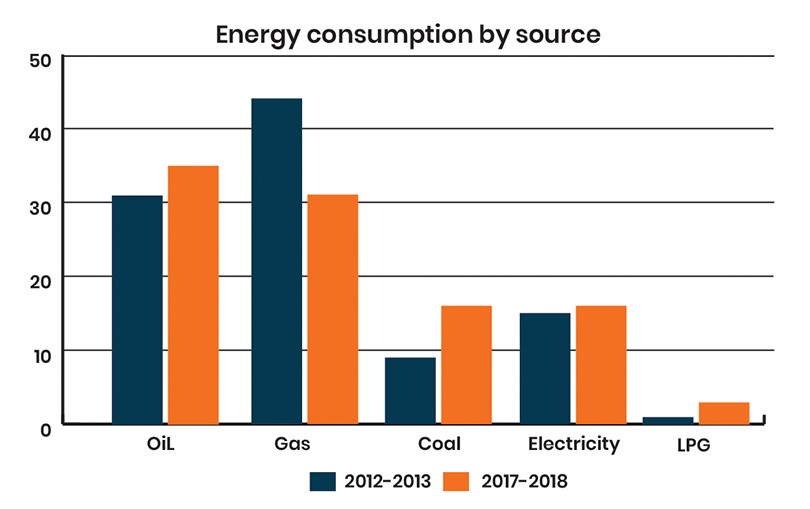

Roughly, 50 percent (about 105 million people) of Pakistan’s population still use biomass for cooking because of low electricity and gas supply. Natural gas plays a significant role in the energy matrix of Pakistan. In 2018, natural gas accounted for an estimated 30 percent of Pakistan’s primary energy consumption, petroleum at 35 percent, and coal at 16 percent.

Pakistan is the 20th largest gas consumer of the world, with an established natural gas industry since the 1950s. However, ironically Pakistan’s gas consumption is nearly the same as in France, which is a developed and industrialized country [with a GDP ten times bigger than Pakistan].

Read more: Government takes credit for “exceptional growth” in Oil and Gas sector

Natural gas consumption has increased from 1,377,307 MMCFt to 1,454,697 MMCFt. RLNG imports have increased to 313,902,345 MMBtu. There was a time when Pakistan was self-sufficient in gas. However, increased domestic demand over time, fueled by cheap mispricing of the natural resource, creation of the CNG motor vehicle industry, lack of alternative fuels, and diminishing production have resulted in increased amounts of imported gas.

In FY18, approximately 7.7 million TOE LNG gas was imported. Currently, Pakistan has over 9 million domestic consumers of gas, and these are growing by over 8% each year. The majority of domestic consumers, around 5.4 million, are based in Punjab; that account for 60 percent of the total domestic gas consumers, Sindh has 35 percent of the country’s domestic consumers at 2.6 million.

Domestic demand has been fueled by politicians all wanting to send cheap gas to their districts, and further exacerbated by rapid population growth and industrialization needs. Punjab province has the highest gas consumption in the country, using 16,241,253 MCFt. The consumption is driven by the power sector, domestic consumers, general industry, and fertilizer plants.

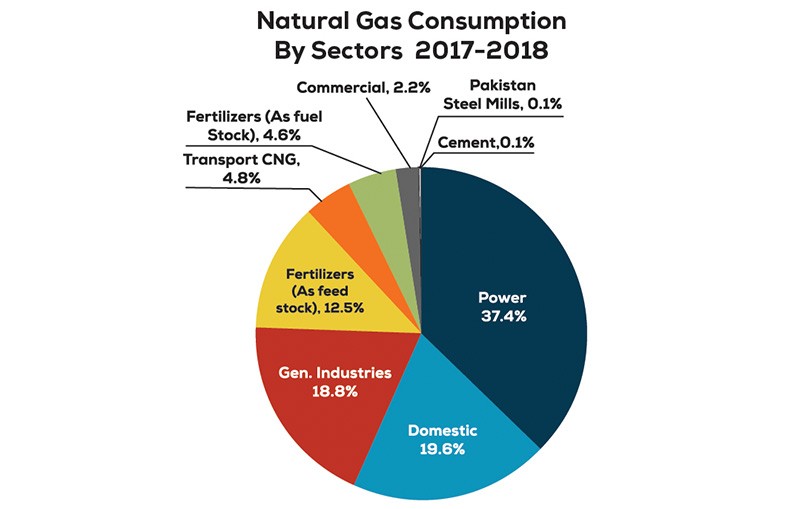

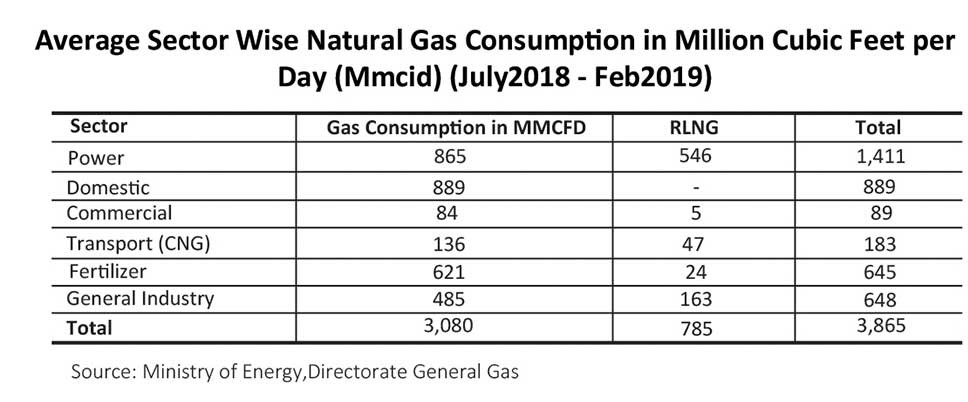

KPK has the lowest consumption of 1,769,151 MCFt, which is mainly driven by household consumption and its transport sector. In Pakistan, the power sector is the largest consumer of natural gas at 37 percent of all consumption, followed by domestic consumers (20 percent) and industry at (19 percent). Overall annual gas consumption in the country is growing at around 6 percent per annum.

Major Players in the market

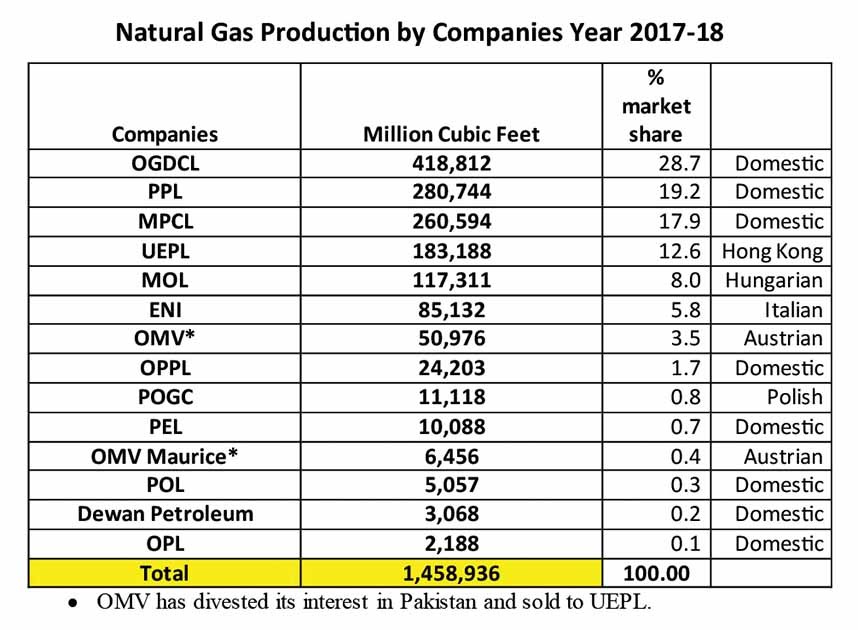

The upstream oil and gas sector is led by the state-owned companies, namely, Oil and Gas Development Corporation Limited (OGDCL), Pakistan Petroleum Limited (PPL) and Mari Petroleum (which is owned by Fauji Foundation and OGDCL). All are listed on the Pakistani stock exchange, and OGDCL is also listed on the London stock exchange. Presently, thirteen major companies are operating in this sector in Pakistan.

There are eight domestic companies, and remaining are foreign (Italian, Hungarian, Hong Kong, and Polish). Pakistani companies are significant players in the gas E&P market. OGDCL is the largest player with 29% market share, followed by PPL at 19% and MPCL at 18%. The largest foreign company is UEPL, with a 13% market share (which is even larger when OMV shares are added), followed by MOL at 8% and ENI at 6%.

In FY18, approximately 7.7 million TOE LNG gas was imported. Currently, Pakistan has over 9 million domestic consumers of gas, and these are growing by over 8% each year

Foreign companies are operating both independently as well in joint ventures with other companies, both local and international. OGDCL is the largest domestic company in the exploration and production segment in Pakistan. It contributes around 29% towards the country’s total oil and gas production.

In FY18-19, the country injected 13 new wells producing 373 thousand barrels of crude oil and 4,867-meter cubic feet gas in its production. The company gathered 1,324 line kilometer of 2D and 620 sq km of 3D seismic data, 63%, and 41%, respectively, of total seismic data acquisition in the country.

Read more: Reports on Oil & Gas discovery in Pakistan untrue!

The company overall has 43 exploratory licenses, the largest exploration acreage in Pakistan, covering 24% of total awarded acreage as of June 2019. Mari petroleum is said to have the highest well success ratio of any E&P company in Pakistan (1:1.44, or 69.23%) compared to other domestic companies, which average 1:3.3, or 30.1%, internationally this ratio stands at 1:8. Currently, MPCL is working in 17 oil/gas blocks, of which MPCL is entirely exploring 11 blocks while in the other six blocks, MPCL is a joint partner.

Gas pricing for producers

Gas pricing has changed over time. In the 1950s-60s, prices were determined on a cost-plus basis. The gas purchase agreement for the Mari field allows a minimum return of 30 percent, net of taxes on shareholder’s funds. Since 1985, wellhead gas pricing has been revised intermittently as per the government policy.

It is linked to a reference crude/fuel oil price taken from a basket of imported Arabian crude oil during the last six months, with an upper cap. Currently, the government’s Petroleum Exploration and Production Policy 2012 is in operation. The industry generally sees the policy as providing attractive incentives for any company to enter the sector, including foreign companies.

The policy specifically aims to promote exploration and production activities by offering competitive incentives to investors. To capture the different risk levels associated with E&P activities in different regions of Pakistan, one offshore and three onshore zones have been delineated. Under the policy, the government has set Well Head Gas Price in Zone-III at $6 per MMBtu, $6.3 in Zone-II, and $6.6 in Zone-I.

The Zone-I comprises of west Balochistan, Pashin, and Potowar basins; Zone-II consisted of Kirthar, east Balochistan, Punjab Platform, and Suleman basins while the Lower Indus Basin falls in Zone-III. The Petroleum Policy also provides a comprehensive pricing mechanism for offshore zones: Zone 0 that has been set at $7 per MMBtu for Shallow, $8 for deep, and $9 for ultra-deep exploration.

Read more: LNG: the Rolls Royce of gases – Dr Farid A Malik

However, prices received by companies are different for each gas field they have, since they are set by the petroleum policy that was applicable at the time when they were discovered. So, for example, any gas produced from the Sui gas field or Mari gas fields found in the 1950s are receiving prices set by the applicable pricing policy at the time.

The issue here is that they are a pittance of those discovered later, and the 2012 rates apply only to those found later. Currently, Mari provides the government with the lowest price for its field located in the1950’s at around $1.40 compared to the 2012 pricing policy, which has set it about $5.70.

Why has Pakistan found it challenging to attract foreign investment?

Pakistan’s upstream sector has not attracted as much foreign investment as expected, despite attractive policies and high equity returns. There have been several hindering factors, as more accessible to develop basins have already been exhausted, and others such as those in Balochistan have law and order issues.

Industry experts believe that Pakistan Petroleum Policy 2012 offers one of the best incentives for E&P companies, and while security challenges do exist in Pakistan, they are manageable. Foreign investment in E&P would have helped to bring in much needed foreign exchange, technical skills, and capital into the country.

However, it has been difficult for Pakistan in the past couple of decades given the law and order situation that has prevailed in the country, especially since 1979 Afghan-Soviet Union war and later the 2001 war on terror. Initially, much of the oil and gas discoveries made in Pakistan were by foreign companies, such as Stanvac, Hunt, Sun Oil, and Esso, etc., that came into the country and developed fields and often stayed until they were depleted.

Risk-Reward of Unexplored Basins

Generally, the basins which were considered valuable – those that had a higher percentage of finding oil and gas – have been already discovered and depleted. The Potowar basin which covers, Jhelum district, Attock, and Chakwal districts – started decades ago, and it is now mostly exhausted.

The remaining basins in Pakistan are perceived as offering higher risk – lower reward returns, especially in light of the security conditions. Basins considered highly prospective such as the Kohat basin and those in Balochistan, are in regions that have remained inaccessible for the past four decades.

Companies have now started working in the Kohat Basin, which includes the Gurguri field ( the last significant discovery of gas in Pakistan found in 1998). It also includes Kalabagh, district Mianwali, OGDCL’s Nashpa field in Karak district, and so on. Other basins include the Upper Indus basin – Qadirpur, Sui, Kandhkot, etc. and the Lower Indus basin, where all discoveries in the Hyderabad districts come under.

Read more: Ogra recommends 47% rise in gas prices – fulfilling an IMF demand?

Currently, Balochistan’s Pishin basin is seen as a precious block; however, while the blocks were allocated in the 1990s, no exploration has happened here due to the poor law and order situation. Nevertheless, as domestic companies start moving in here and finding hydrocarbon finds, foreign companies are also expected to join over time.

Generally, when discoveries are made in a basin, it propels other companies to jump into the same basin; since they now think there is a higher probability of a breakthrough. It has meant that suitable basins are first explored and left when depleted.

Offshore disappointments so far

Pakistan so far has had zero discoveries in its waters and given that offshore drilling is exceptionally costly. It is difficult to find companies that wish to come in for investment in this area. Internationally, some governments offer inducements to attract foreign companies and to increase the amount of exploration done in offshore regions.

The government may return a specific percentage – often 35-45 percent – if the well comes up dry so that the company does not make a complete loss. It does not happen in Pakistan, which limits the growth of offshore drilling.

Having said that, early 2019 saw substantial investment in the offshore Indus basin near Karachi, by OGDCL in a joint venture with American company Exxon and Italian company ENI, conducted offshore exploratory drilling.

These came out dry, but an estimated $95m was spent. By comparison, drilling cost is much lower onshore with costs in the region of $25-$30 million in the Potowar region where drilling wells are usually around 6,500 meters but only $6-$7 million in Sindh where many fields are about 1500 meters deep. The government has announced it will offer another 35 sites for potential offshore exploration and 10 for onshore exploration.

Challenges for Increasing Production

Concerns exist about Pakistan’s wells running dry in the next decade. However, this is based on current production and technology. Large areas in the country remain unexplored due to security, the structure of the bidding process for the blocks, and the government’s role in state-run companies.

Read more: Government should have one Export Policy for all sectors of Industry

Market prospects hinge on safety

E&P companies in Pakistan think there are many undiscovered areas in Pakistan – Geological surveys show that vast potential reserves exist in Pakistan with potential estimated at 300 TCF versus the 54 TCF discovered so far. Baluchistan has large areas still unexplored, especially in the frontier.

Only central areas like Sui have had discoveries so far – there are many frontier regions or regions like Kalat, Naran, Kohlu, Kharan, etc. where companies are only now going into the region. Some of these areas are close to where Iran also has gas fields, so the expectation is, and data also supports that gas discoveries can be made there.

The only thing stopping development so far is the law and order situation. The government needs to work on increasing safety in untapped areas actively. Currently, companies pay substantial percentages as a security cost to FC, often as high as 30 percent for the cost of developing wells. An estimate given by Additional Secretary In-charge of the Petroleum Division Mian Asad Hayauddin to the Senate put the estimated total cost to the petroleum companies at Rs14bn.

More significant development and exploration cannot happen unless the government improves the overall security situation. Earlier this year, the government announced it would set up a special security force of 50,000, this the Senate committee was told, would ensure that the needed seismic and exploration surveys (of all no-go areas) would be complete in seven to eight years.

Mian Asad Hayauddin said that otherwise, the existing force of 250 security personnel would take 780 years to do the same job. Recently, Mari has started conducting seismic activity in the tribal areas in Wana and has gone into Kohlu – block 28, which was allocated in 1985 by the government. No work, including no reconnaissance activities, were done so far because of the difficult terrain and infrastructure challenges due to the lack of law and order.

Read more: Modernizing the power sector of Pakistan

The estimated discovery of gas, thought will be at least three TCF in Wana since it is close to the Gurguri field. KPK frontier regions are also thought to have abundant gas or oil potential. Currently, 40 percent of OGDCL total production is in district Karak from one field Nashpa at 27,000 tons per day; they also have around 200m natural gas and LPG 300 tons per day. Industry experts believe that a lot of potential discoveries can be made in the frontier tribal areas, in the south of KPK, and the Balochistan areas close to these tribal areas.

Bidding of Blocks for ‘farming’ and not exploring

The process for bidding for blocks – without paying for them means that companies bidding for blocks do not pay the government upfront cost for it. Instead, they submit a work plan saying they will drill a certain number of wells in a certain period. The winning company is generally one that commits the most – states it will do the largest number over the shortest period.

However, while tens of blocks, if not more that are owned by companies for decades, have had no work started on them, while the government has clauses in the contract that can penalize or take back blocks, it has never really enforced these and not taken one back in decades. Even OGDCL has over 150 blocks from the government.

Furthermore, the government’s 2012 petroleum policy, which tries to encourage indigenous companies to develop expertise in the field, has also inadvertently helped ‘smart trading’ companies buy blocks, which they do not develop, but rather wait for other companies to enter the area, and develop its potential so that they can sell share of their block to other partners taking a premium.

It has encouraged some very small players in the market bidding for and winning blocks, such as Shahzad International (Petroleum Exploration Ltd) or Al-Haj group (Al-Haj Enterprises (Private) Limited (AEPL)). The latter company otherwise operates in Pakistan’s logistics and oil and goods transportation sector. Often have blocks which to date have not been explored or developed.

Government bureaucracy stultifies growth

The importance of adopting new technology in this field cannot be underestimated. The industry is capital and technology-intensive; the latest technologies need to be used in all stages from seismic and exploration to development stages. For Pakistan’s E&P sector – the fact that its two major companies are state-run companies, PPL and OGDCL, that are subject to government rules, especially on procurement, act as hinderances to further development and discovery of fields.

The companies do not invest in the latest technologies often due to fear of government bureaucracy and NAB. The industry has to pay hundreds of millions for the newest equipment, and the state-run companies often lag in adopting the latest technology, which would make them more efficient and produce more.

Read more: With rising gas prices, all eyes on TAPI

This is often due to the fear of justifying themselves to NAB why ‘expensive’ equipment was bought. Using the latest technology may save the company months in their project delivery times, but they fear to explain that to civil servants who cannot envisage expenditure of billions. Also, PEPRA rules insist that the government buys from the cheapest source, with not enough taken account of the quality of the product or services delivered.

The ubiquitous circular debt issue in the energy market also affects the E&P sector. State companies like OGDCL have increasing amounts of receivables from refineries, power sector, and the gas distribution sector. The consequent tighter cashflow affects the companies’ liquidity and ability to invest further in technology and development of wells etc.

Another ubiquitous complaint from the government is that its approvals process is very lengthy, and at each stage, companies have to get government approvals for work. When the company, for example, goes for surveys, it has to inform the government, what it finds, submit reports, start exploratory wells, and so on. Most companies are especially frustrated with delays that occur, especially after discoveries.

On average, it takes six months – 1 year to approve documentation. An example given by one industry expert was after Mari found oil near Mach district, last October. After the discovery within one month, they had set up storage tanks, separation facilities to separate, oil, gas, water, etc., but are still waiting for approvals to sell that oil.

Read more: Pak-Iran: energy sector performance and wind power project

They have to sell oil to refineries, but no refinery is willing to take that oil since it does not meet its specifications for the refinery. Worst, the company is not allowed to sell elsewhere or even to export it to markets that can deal with those specifications.

The government also sets a minimum price below which you cannot sell, and the refinery industry is not buying at that price. So, oil is stuck in well in the meantime.

If they discover gas, then they are dependent on the government providing pipeline infrastructure to take gas out. E&P companies can send directly to fertilizer companies, power plants; otherwise, all goes to SSGPL and SNGPL. What the government should do is to coordinate development in blocks so that it can set up necessary infrastructure rather than one pipeline for one company.

Najma Minhas is Managing Editor, Global Village Space. She has worked with National Economic Research Associates (NERA) in New York, Lehman Brothers in London and Standard Chartered Bank in Pakistan. Before launching GVS, she worked as a consultant with World Bank, USAID and FES and is a regular participant of Salzburg Forum. Najma studied economics at London School of Economics and International Relations at Columbia University, NewYork. she tweets at @MinhasNajma